Color Grading In Post-Production

Adopting New Technology

This paper considers the adoption of new technology, with specific regard to the advancements made in software color enhancement. It follows on from my paper “Software Color Correction”.

Careful what you wish for:

DEFINITIONS:

DI stands for Digital Intermediate and refers to the digital master from which a film intermediate is recorded. However, for the purpose of grading workflows, I prefer to interpret DI as Data Intermediate. The data interpretation more accurately fits both film and tapeless workflows.

EDL stands for Edit Decision List. The most basic CMX EDL is a simple list of edits for a single video track. More modern versions in AAF or XML formats define multi track timelines and a range of sophisticated effects.

S3D stands for Stereoscopic 3D, meaning digital cinema formats that use a combination of two images to create left and right eye parallax and the illusion of depth. Viewing nearly always requires glasses to separate the left and right eye images. The glasses use colored filters (anaglyph), polarized filters or synchronized shutters to separate a pair of images. The use of two images adds just one of many clues to depth perception. True 3D would mean that a change of position would reveal more information, allowing the viewer to see behind objects. Holograms, which do reveal spatial details, are not yet used in the motion picture industry!

In “Software Color Correction” I outlined the benefits of moving from hardware grading systems to software systems and discussed the advantages it would bring to colorists. The new tools and features available in software systems today surpass both the most optimistic wish list of 10 years ago, and our expectations of five years ago. By comparison the impact on color grading has been less dramatic. Why has such an obvious improvement in technology not been matched by an equally significant advance in the art of color grading?

Sometimes sitting in front of my grading system, with the latest software update and faster graphics card, I feel like I am sitting in a Bugatti Veyron on a motorway with road works, average speed cameras and a 30 mph speed limit.

There are a few cases where production companies have invested in their own grading system, hired a colorist and then spent six months to a year working on a project. There are also some facilities that do maximize the benefits of software grading. However, instead of a carefully planned DI grade, many productions only remember color enhancement as an after thought. There is an old equation:

Quality = Budget x Time

If there is no time and no budget, it is not hard to figure out the quality. This is a shame since color enhancement offers great production value. It is even sadder because the old equation needs modifying for the modern software facility:

Quality = Planning* {Budget x Time}

*including planned use of a high-end software grading solution

In other words poor planning will cost an almost infinite amount and still take an eternity to achieve mediocre results. Careful planning on the other hand can cost less, take less time and still look better. That combination does not happen very often.

Integrated Workflows

As expected, software grading systems are much more common than they were five years ago. In fact they are being installed faster than any of the hardware systems ever were. There are many reasons; they are cheaper, they require less ancillary kit, they are easier to maintain, and most importantly they are easier to use.

The next step must surely be to adopt new workflows rather than adapt old ones.

When color grading moved from analog to digital processing it was a matter of removing one box and replacing it with another. The digital processing allowed new tools and features, but to a client nothing changed, even the panels looked the same. The transition from SD to HD was even easier. Whilst older (hardware) systems had to be exchanged, many were HD ready and just needed a license or board upgrade.

Making open architecture software that can replace dedicated hardware without the need to disrupt the existing workflow has facilitated the acceptance of software grading. Post-production facilities wanted tape input, VTR export, telecine control, timecode regeneration and audio support, all of which are taken for granted in a traditional telecine room. In truth, many of these features are handy but not essential in a DI environment, but few were prepared to embrace a totally new workflow without the safety of the old workflow. Most adopters can see the promised future, but want to get there with baby steps. Consequently, many of their clients are not aware of the benefits of a fully integrated DI grading.

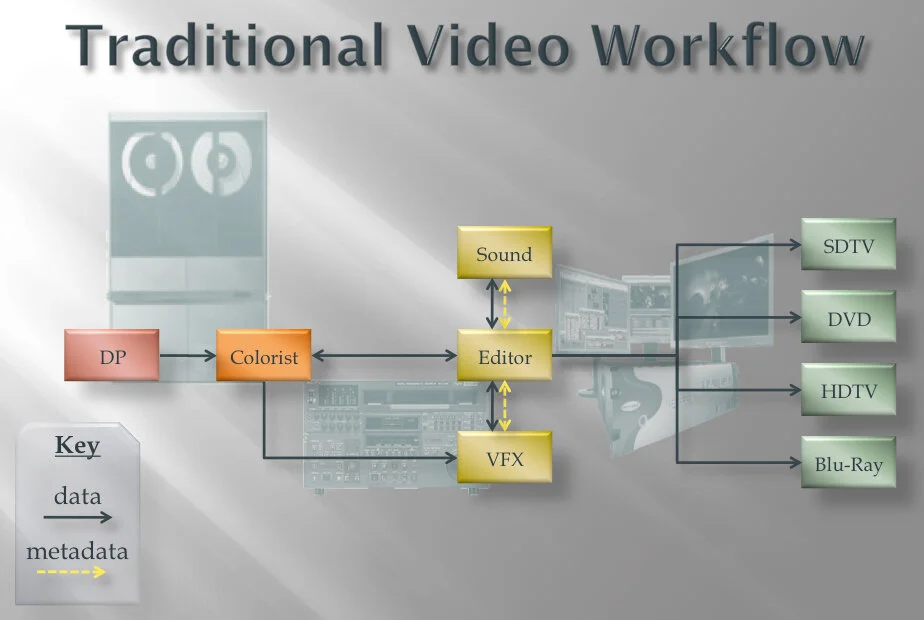

The traditional telecine workflows depended on very expensive hardware setups, and were quite isolated from the rest of postproduction. Colorists graded directly from the telecine to tape, or from tape back to tape. For a detailed description of the various workflows refer to “From One-Light To Final Grade” The consequence of adapting software to work in old workflow models is that many of the limitations of the telecine suites have been inherited, not removed. For example, there is very little exchange of metadata in the old linear workflow. More often than not even the EDL is printed on paper rather than imported into the timeline. The next step must surely be to adopt new workflows rather than adapt old ones.

The candidates for early adoption of the pure data workflow tend to be small boutique companies and start-ups. They have led the way, proving that sometimes it is possible to spend less money, and yet provide a faster, higher quality service. It’s not quite that easy of course; all the successful boutiques have highly skilled artists that probably would have succeeded anyway. The significant fact is that software technology has removed cost as a barrier to entry and made the owner/colorist facility feasible. I recently graded “The Wake Wood” at one such facility, The Post Republic in Berlin.

The film has a large number of VFX shots, but the main grading was done as soon as editing was complete, which was before all the effects had been finished. Camera original media was first conformed, and then graded in the Film Master DI theatre. Theeditor and director noticedseveral problems with shots on the projection screen that could not be seen in the edit room. It was very easy to change these shots at the same time as the VFX shots were added. The Wake Wood contains many day-for-night shots that were scheduled for sky replacements and VFX treatment. However, it became apparent that there was not the time or budget for the team to do everything on the list. A final color session was already planned for when the effects work had been completed, so this was bought forward and I was able to do some simple composites, and many of the day for night shots as part of the grading. On other shots the VFX team produced sky mattes for me to grade with, rather than doing complete sky replacements. These added very relatively little time to the grading session, but released a great deal of time for the more crucial VFX shots.

Before and after grading from The Wake Wood: The shot required luminance keys, and several shapes to darken the sky and landscape. The headlamp spill on the road is done with two auto tracking shapes and some key frames to create a more realistic bounce over the road surface. The whole effect was achieved in the grading suite.

Competition

Of course the manufacturers of an increasing number of color systems are competing for all sectors of the market. It was a popular belief that the market could not support so many products, and indeed several of the manufacturers have been acquired. Acquisition is a mixed blessing. All of the buyers of color grading companies have some sort of existing interest in the technology and the industry. In the case of Digital Vision acquiring Nucoda (2005) there was a perfect fit. Digital Vision is a market leader in restoration and noise reduction, with experience of VTR control and videotape formats, and they manufacture their own control panels. Nucoda had an established color corrector, with data conform and an AAF multi-track timeline with support for color management and OFX plug-ins. Other company mergers have a less obvious synergy and have led to reduced development, weaker support, redundancies and concern over the future. Nevertheless, none of the grading systems have disappeared and we continue to see new ones introduced.

Color systems compete for sales in 3 ways. Inevitably some compete on price, but it is becoming clear that a cheap system does not necessarily generate more profit. The cost of a colorist, control panels, cutting edge hardware, storage, monitoring and a viewing environment mean that, even with free software, overheads are not low and it is not practical to do a job at half the price in twice the time. Small budgets need speed even more than big budgets, and the lower profit has to be offset with higher volume.

Stability, support and sustained development should be deciding factors in a purchase decision.

Another selling strategy is to focus on niche markets, with a view to anticipating future trends. This does give a company a little breathing space especially if that market proves fruitful. However, as soon as a market shows growth, all the other companies jump in too. One of the reasons we wanted software was the relative speed and ease of adding new features. Five years ago only one software color corrector promised telecine control, now at least 3 do. Not long ago only one system promised dedicated S3D tools, now stereoscopic support is commonplace.

In the long term a grading system must stand out on its flexibility and features. It must offer great integration not just into current workflows but also future workflows, formats and facilities. It must support increasingly complex edit decision lists, interface well with new digital cameras and of course develop new features for new markets. Manufacturers of high-end systems are also expected to provide 24/7 support and bespoke solutions to individual problems. Ten years ago only a few grading systems could comfortably deliver consistently good results in a reasonable time, now almost all of them do. Stability, support and sustained development should be deciding factors in a purchase decision.

High-End Grading

Integration, not cost, is actually what separates the low-end systems from the high-end. Many machines simply grade a stream of images and need the rest of post-production to work around them. A high-end system is flexible enough to fit into any postproduction chain without compromise and is usually able to finish the job and export the deliverable masters. To get exceptional results, a colorist must be able to see what the audience sees. It follows that the one place that displays a project in a controlled viewing environment with calibrated monitoring is the DI grading suite. It is common sense then that all decisions and approvals should take place in that same DI theatre, and since high end grading systems can now read edls, mattes and composite elements it makes sense that the postproduction supervisor works very closely with the colorist.

There are three areas of integration to consider:

Sources

Conforming

Finishing

Sources

Recent years have seen significant improvement in data cameras, and a huge growth in the number of productions that use them. These cameras usually record raw data and the metadata to debayer and interpolate it. To get optimum results the color correction system needs to access both the raw data and the camera metadata. Ideally it should also read metadata changes from a dailies system, and let the colorist make changes too. The Film Master for example, accepts native files from:

Vision Research: Phantom camera

Red: Red One and Mysterium

Silicon Imaging: SI 2K

Arri: D21 and Alexa

Sony: XDCa

And it offers extended metadata support for Codex and Keyframe Concept on set devices. It can also read and write .dpx, .tif, .jpg, .rgb, .exr, .mxf and .mov files as well as .edl, and .aaf lists. Like most systems it imports .cdl values, but it can also write .cdl metadata. This level of flexibility improves quality, efficiency and of course workflow integration.

Conforming

For the colorist the biggest difference between the traditional workflow and DI is the use of a conformed timeline. Conforming in a grading project means more than working in context. When a job is imported from tape, or as a flattened edit, there are many disadvantages, more than there is space for in this paper. A few examples will have to suffice; files are less likely to be compressed or pre-graded; grading before applying a transition is quicker and cleaner; over length clips are better for motion estimation algorithms used in noise and grain reduction; edit changes and VFX updates are easier to manage and valuable metadata is preserved.

Finishing

There is evidence that our viewing habits are changing, but not necessarily as fast or as profitably as the providers would like. Blu-ray was supposed to encourage everyone to buy their favorite movies again, a repeat of the switch from VHS to DVD. However, it might never happen. There is a strong trend towards downloads and on demand viewing rather than purchase or rental. On-demand usage soared 20% in 2009 and is also more profitable for studios than traditional rental. By comparison, rental company Blockbuster recently warned that competition and declining sales “raise substantial doubt about our ability to continue as a going concern.”

Online viewing makes restoration and re-mastering a possible growth area, but according to the New York Times “…only Warner Brothers and Sony (the owners of the Columbia films) are maintaining a truly active library program… Turner Classic Movies online says that of the 162,984 films listed in its database (based on the authoritative AFI Catalog), only 5,980 (3.67 percent) are available on home video.” There are plenty of titles waiting to be digitally mastered, hopefully before they fade away. It certainly makes sense to have a suitable toolset for both old and new assets.

StreetDance 3D was shot stereoscopic with Red cameras, and was conformed and graded on Film Master at The Post Republic.

The current industry favorite is stereoscopic 3D. There has been a steady growth of 3D capable theatres in the last five years, and 2010 is witnessing a remarkable S3D boom that started with “Avatar”, the top grossing film of 2009 and the fastest film ever to take $500 million at the box office. The top grossing film of 2010 so far is Tim Burtons 3D “Alice in Wonderland” and the top four films in the first quarter of 2010 are all S3D2. There are at least 20 more stereoscopic blockbusters planned for this year, but it is not the first time that 3D has been pushed. Charles Wheatstone first described stereopsis in 1838 and showed stereo drawings with the aid of the first stereoscope. Cinemas promoted stereoscopic films in the 1890s, the 1950s and the 1980s and Imax has kept the idea going. However, digital projection makes it a lot easier to show S3D movies, hence the optimism for its latest renaissance. Similarly DI workflows make the postproduction much simpler too.

The majority of colorists now work with software grading systems, and more and more of the projects we color require a fully integrated DI treatment. Digital cameras, and stereoscopic media will accelerate the inevitable change to informed color enhancement, and in the meantime there is an opportunity to get better quality and flexibility in less time for less money. Make sure that you are not missing out; plan to make the most of your grade.

Happy Coloring!

Sources

New York Times (March 17, 2010)

Box Office Mojo

New York Times (December 30, 2009)